Crawling Inwards: An Analysis of Invisible Illness as Body Horror.

(an essay on body horror through the perspective of a type 1 diabetic)

hey, friend. it’s been a while. i’m nervous to release this because i haven’t written in a hot minute, but the only way forward is through. thank you for being patient with me.

all my love <3

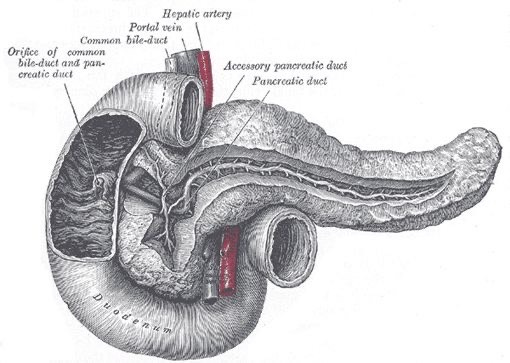

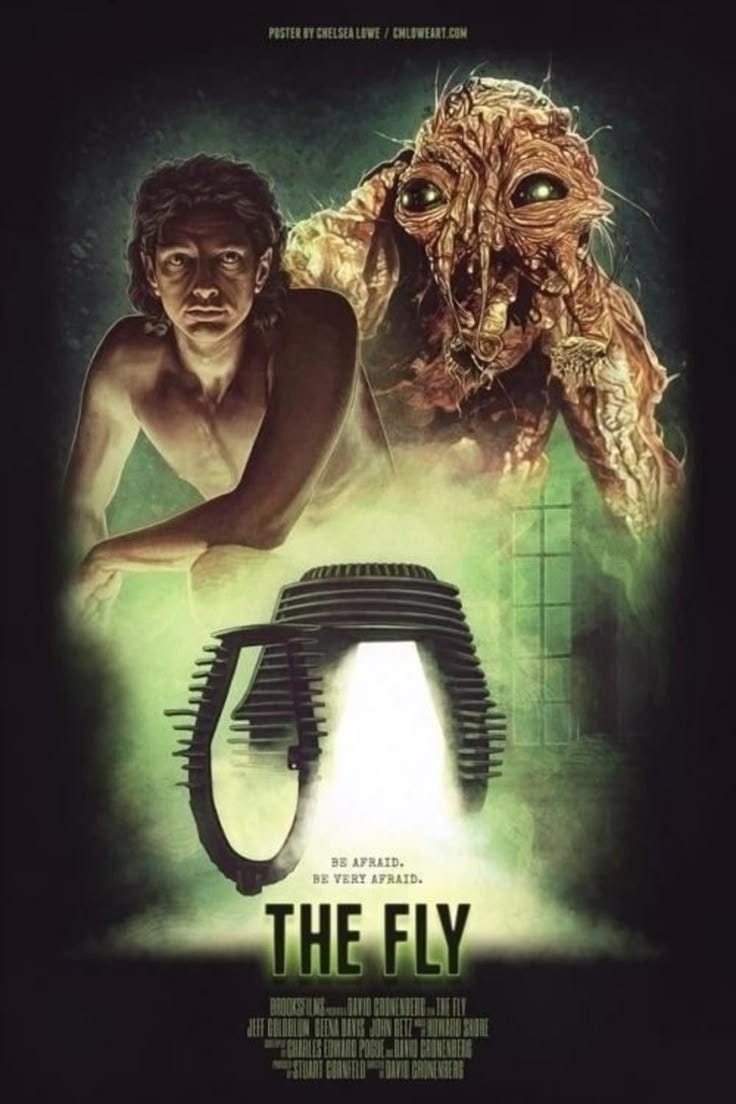

content warning: the films, images in this essay and descriptions of medical challenges will be gore-adjacent at varying degrees. needles, anatomy drawings of organs and other medical equipment might be mentioned or shown in passing as well. the theatrical features of body horror include outlandish and disproportional physicalities, unusual or strange textures, bodily fluids, therianthropic forms (half-human, half-animal) and the occasional nude body. be mindful x

an invisible disability or illness is often defined as a physical, mental, or neurological condition that is not visible from the outside, yet can limit or challenge a person’s movements, senses, or activities. due to these illnesses being ‘unseen’, false perceptions, judgements, and misunderstandings are a common occurence in the life of someone with a chronic illness that is hidden.

paraphrased definition drawn from Jennifer Steiner’s blog post: ‘‘But you don’t look sick’’ — and other challenging misunderstandings about invisible illness (2021) and the Invisible Disability Association (IDA)

body horror, sometimes referred to as biological horror, is a subgenre of horror fiction that emphasises the grotesque or psychologically disturbing alterations of the human body, or any creature for that matter. the subgenre has garnered a witty, detail-oriented audience over the decades, and shies away from cult slashers like Dream Home (2010) or My Bloody Valentine (1981). i think it leans into a frank and curious world of change. one where terror and vulnerability are the truth and reality takes a mortal form in its personification. it also produces works that tow the line between being physically stimulating and deeply perplexing, yet they never stray from the fundamentals of the human condition. motifs are often as straightforward as innate desire, understanding, or traversing through the mundane, all whilst maintaining a sense of edginess and ambiguity.

before i proceed, you may not know that i am a type 1 diabetic. this integral yet subdued part of my life means i rely on insulin to stay alive, much like we need air to breathe or water to drink. referencing the audience i mentioned earlier, body horror is often praised by fans with chronic illnesses and disabilities. the physical changes that protagonists undergo seem to mirror, at least in my opinion, the unexpected and frustrating changes we adapt to in our daily lives, as people with pressing health dynamics and challenges. it is by no means a simple feat to wake up and convince yourself that your body isn’t your worst enemy. by that standard, also acknowledging how sensitive and responsive it can be, too.

as such, body horror as an art form serves a purpose much greater than it likely anticipated itself to: it speaks on behalf of the disenfranchised, the exhausted, those in search of solace without pity and remedy without complex atonement. which is hard, might I add. having your autonomy stripped from you continuously like that could cause anyone to lose their mind. they might seek unrelenting retribution of some sort, whether it’s with God, the global healthcare conglomerate, or just tone-deaf people who swear they can heal your pancreas with cinnamon, garlic cloves, and berberine. speaking especially for those with invisible illnesses, there is an uphill struggle (cause the language of war does not fare well with me in the case of my health) that body horror narrates strategically, and it finds a way to represent both our turmoil and the little pleasures in that walk.

understandably, body horror has grown to serve a purpose much more intensive and particular, compared to its slasher and erotic horror predecessors. in the case of visual media, it is not a common occurrence that something frightening and physically provocative strikes the balance of being both entertaining and attentive to its othered audience. it has a subtle flair for drama, performance, and boldness, all without being unaware of its deeper tenor. it allows individuals with invisible illnesses and disabilities to find themselves in the storylines and a sense of nearness to our lived experiences, without making a tacky commodity of the viewers. if anything, it respects its audience.

the phenology of identity in body horror is particularly important here. basically, the cyclical nature of identity and how it endorses the character’s development is central to the symbolic meaning of the body changing in the way it does, and inevitably, the psyche of the character as well. it raises an essential question for me: how does the phenology of identity in body horror connect to the experiences of those with invisible illnesses? for one, this subgenre is so incredibly fluid that it can, at any moment, decide to abandon a sense of binary or typical narrative structure in how the characters define themselves. once said character reaches a point of no return, where they’ve officially submerged themselves into an identity, or a belief about what or who they are, their development takes on a fantastical quality of being firm and unrelenting in its existence.

let us make an example of Suspiria: we see a thoughtful and unsure Suzy move into a dance residency in West Berlin, amid political violence and unrest. without spoiling the films, in both the original Argento film and Guadagnino’s remake, she has this discerning, but deer-like quality to her. she isn’t fragile, just slow to the process. Suzy behaves in a way that communicates that her curiosity is far larger than her unfamiliarity. she appears eager sometimes, then fully unwilling in other regards. pardon my cheesiness, but she truly is dancing with her environment, and the audience is witnessing and experiencing this with and as her. as she comes to learn who the matron teachers are in this residency and what they really do, we watch as Suzy submits to this reality. and after her submission, she becomes it.

speaking from experience, i know what it is to be brought to my knees by something far more aggressive than myself. health challenges feel like a pendulum swinging, and there’s no way to stop it; there is only the ability to learn that uncertainty and consistency exist in varying degrees on this swing. just as there are days and even weeks when one can be completely in sync and consistent about their health, there are also seasons that drive you to insanity and submission. what draws me to Suzy in this case is how her submission wasn’t about giving up; it was about responding to a change that was already calling her. the change was inevitable. she was going to embrace a new reality regardless and the only thing she could shift was her response to it. i think in many ways, this answers the question of what is at the centre of that phenology of identity. change. change is non-negotiable, and under as fluid an environment as in body horror, it is but a candelabra in the main hall.

commonly, body horrors tend to have Western and white protagonists, but there are still plenty of stories that centre other communities; it’s just less common. i think this makes for great grounds to interrogate the dimensions of self-awareness that these fictional stories have, especially as they rely on said communities for understanding and narrative influence based on social situations, philosophies of the mind and body and even just exploration. this can be said about many art forms and genres. however, it strikes an interesting chord in body horror because of its proximity to those who are othered or excluded.

my dissertation explores the thematic space of healthcare and migration, and i think vividly about these factors in the context of body horror. as i contemplated writing this piece, i wondered where i, as a Black, chronically ill South African woman, fit into the grand scheme of understanding the body [objectively] as it relates to this subgenre. i also considered how much of this could be a comment on the exclusion of Black and brown bodies in healthcare and what that might signify. these are the kinds of stimulating conversations that body horror can generate for the viewer. breaking down these thoughts made me realise that the more reliant you are on systems and external factors outside your physical, financial, and emotional jurisdiction, the more vulnerable you become. health and horror centre these ideas quite naturally. there’s a symbiotic relationship between submission and freedom that exists in both body horror and healthcare, which is fun to think about.

it is also worth noting that body horror teases depth and substance in the protagonist’s journey, right down to their bones. we see them interact with and feel their environment. we also watch as the past, present, and future become a bodily sensation. this is a thoughtful way of drawing the viewers into each scene and making us more aware of our own bodies, as the characters are with theirs. of course, for those of us with invisible illnesses, this has the potential to take on a pseudo-autobiographical eeriness. we feel, not as them, but as ourselves. almost like the narratives are written with us in mind, and the stories have become ours. there is a collaborative quality to this, all without its usual features of teamwork: the audience doesn’t need to be part of the filming process, nor do we need to interact with the script. however, our bodies become tools for production. the cards we’ve been dealt in our health journeys, though major and impactful, fall into the background, and the current feelings coursing through our bodies slither toward the curtain. that presence is what gives identity to body horror. it’s as though we are emotionally mutating into the piece, like some quantum biology experiment.

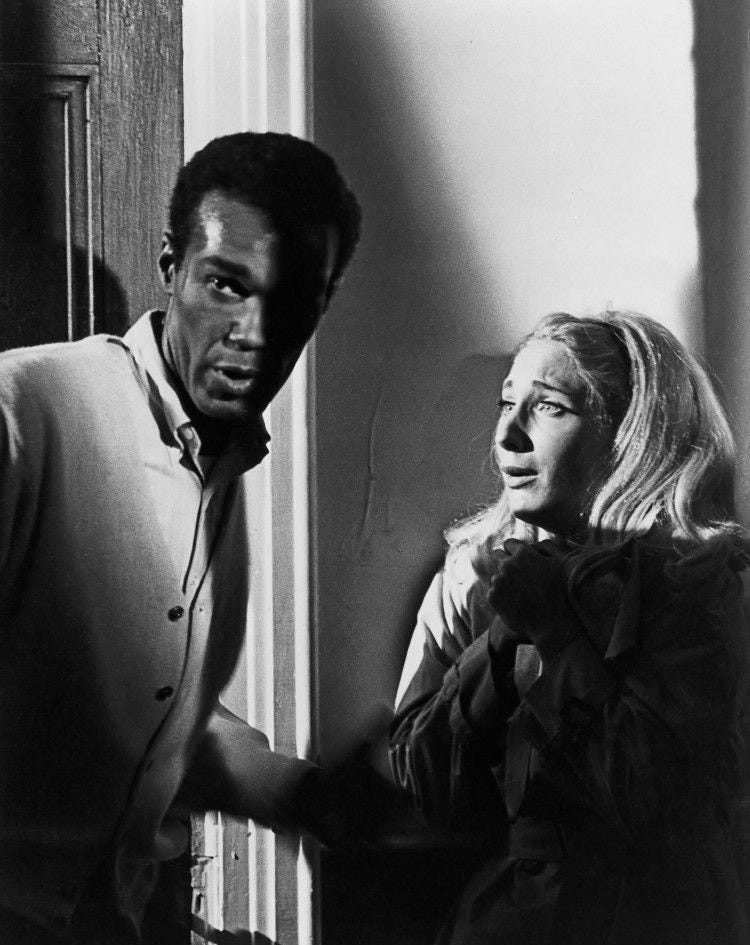

this leads me to a broader point: the body cannot evade consequence. risk is a tricky term for anyone, but particularly for me. it reflects back on itself, presenting an image of the autonomy that disappears amidst the noise of your daily existence as someone with an invisible illness. as you watch Dr Hess Green in Ganja & Hess (1973) take the risk of leaning into his desires and connecting with Ganja, there’s a brief thrill that courses through you. witnessing someone plunge into risky, life-altering choices, like drinking blood and falling for a recently widowed woman, creates a moment of ecstasy. this moment highlights the intensity of living a life that embraces consequences, unafraid to dive headfirst into the unknown. if anything, this goes to show that the body truly is a temple of absolute experience, one that cannot be framed with moral inquisitions and hypotheticals. body horror does a brilliant job of emphasising this.

i’d like to end with the idea of rebirth in this subgenre. slightly on the nose, given this is the end, but i like that. people with invisible illnesses and disabilities are forced to exist in new ways all the time. personally, i struggle to differentiate between the versions i fear and those i don’t. in body horror, this concept is quite prevalent; the protagonist is reborn and that birthing is not ordered or neatly packaged. something i noticed was that they often turned into the thing they feared most. not the creature or gorish entity, but the spirit with brevity and conviction. the more confident, sometimes brash version of themselves. we seem to be afraid of these people, of us, even when we want so badly to be them. having a chronic illness means being that person when you need to, because that conviction is life-saving. in a sleu of self-annihilation, health extremism, rage, the paranoia of loved ones obsessively worrying over you, medical gaslighting, and being at the whim of a body that reacts and counteracts, brash is precisely what you are forced to become.

i would like to encourage you to go and watch the films i’ve mentioned or shown in this piece, as they are stellar. body horror is a subgenre that needs no explanation, for it honours a diverse range of human experiences in a personable, fun and intellectual manner. it is one of the only genres i consider a worthy narrator of my own health and personal development journey. i could argue that other silent voices in the film community would say so as well. my wish is that we are reminded of the importance that art plays in representation, and people say this all the time, but it doesn’t make it any less dire. body horror is to an audience with invisible illnesses, as a shard of glass to a person surrounded by white walls. an opportunity to see oneself again.

yours,

Thando. x

Another beautiful piece.